CLICK HERE FOR PRINTER FRIENDLY VERSION

The current economic uncertainty has never made it more important for creditors to be aware of the most effective way to enforce their foreign judgments in Australia against Australian debtors, particularly once we are in a post-coronavirus world. We set out here (i) how an overseas creditor may enforce foreign judgments in Australia, and (ii) how a debtor may challenge the enforcement of a foreign judgment registered in Australia. We also discuss the inherent complications associated with enforcing Australian judgments overseas, and common prerequisites when doing so. Finally, the article considers arbitration and the enforcement of arbitral awards as an alternative.

Australia is not party to the Hague Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters 1971.

Creditors instead can enforce foreign judgments under:

(a) the Australian Foreign Judgments Act 1991 (Cth) (FJA) only where the judgment has been made by a court specified in the Schedule to the Foreign Judgments Regulations 1992 (Cth) (Regulations); or

(b) the Trans-Tasman Proceedings Act 2010 (Cth) (TTPA) for New Zealand judgments in addition to enforcement under the FJA; or

(c) pursuant to established common law principles otherwise where the above do not apply.

35 foreign jurisdictions are listed in the Regulations,[1] but only six of these are within Australia’s top ten trade partners – Japan, South Korea, United Kingdom,[2] Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore together with France, Germany, Israel and certain Canadian provinces, but what is more surprising is who is not on that list. Currently, for example, China, the United States and India do not fall within the ambit of the FJA.

However, due to some of the limitations that can be experienced in enforcing foreign judgments under the FJA and common law in Australia, parties should also consider including international arbitration as the dispute resolution mechanism in their contracts. This can allow parties the benefit of the enforceability of arbitral awards under the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, known as the New York Convention. At the date of writing, there are 163 countries party to this convention, including each of Australia’s top ten trade partners, with the exception of Taiwan.

A map comparing the enforceability of foreign judgements and foreign awards is below:

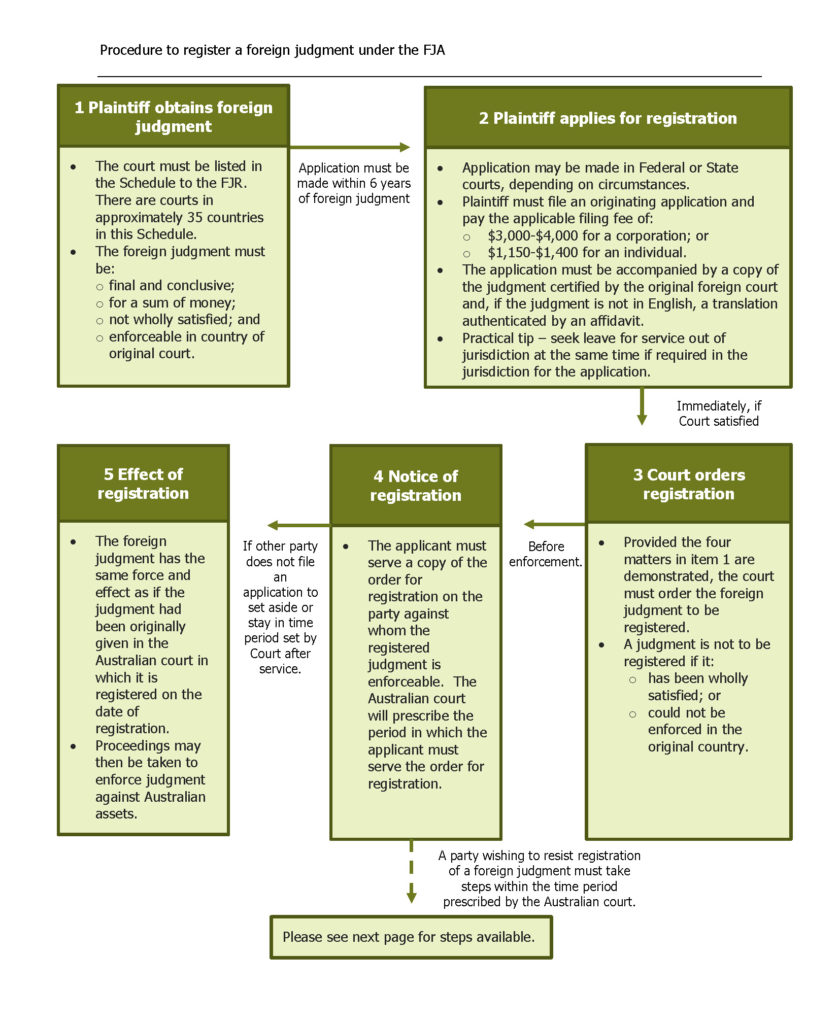

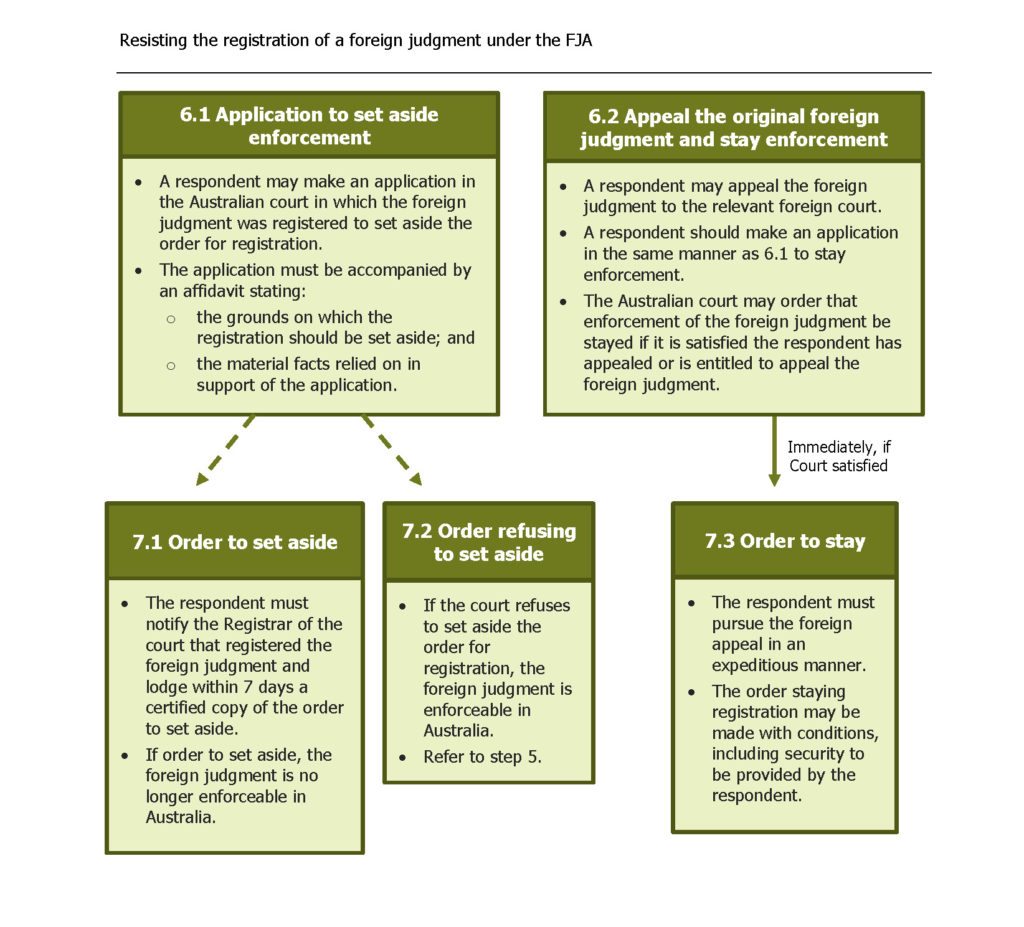

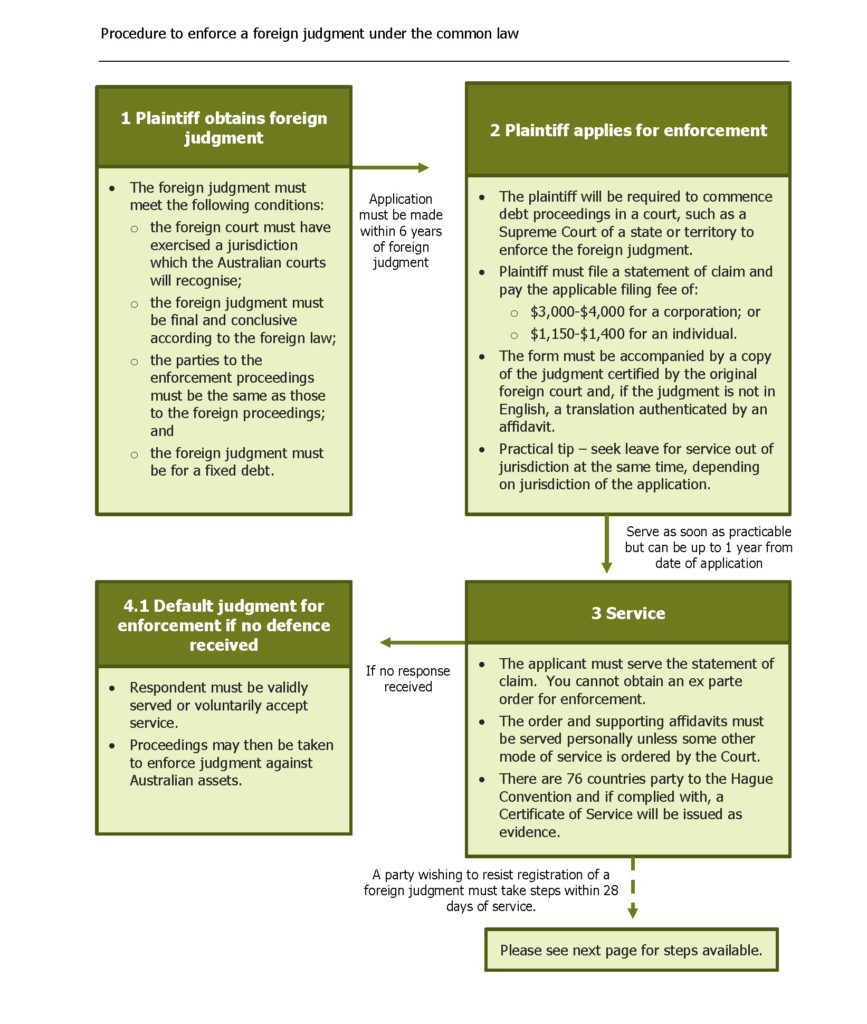

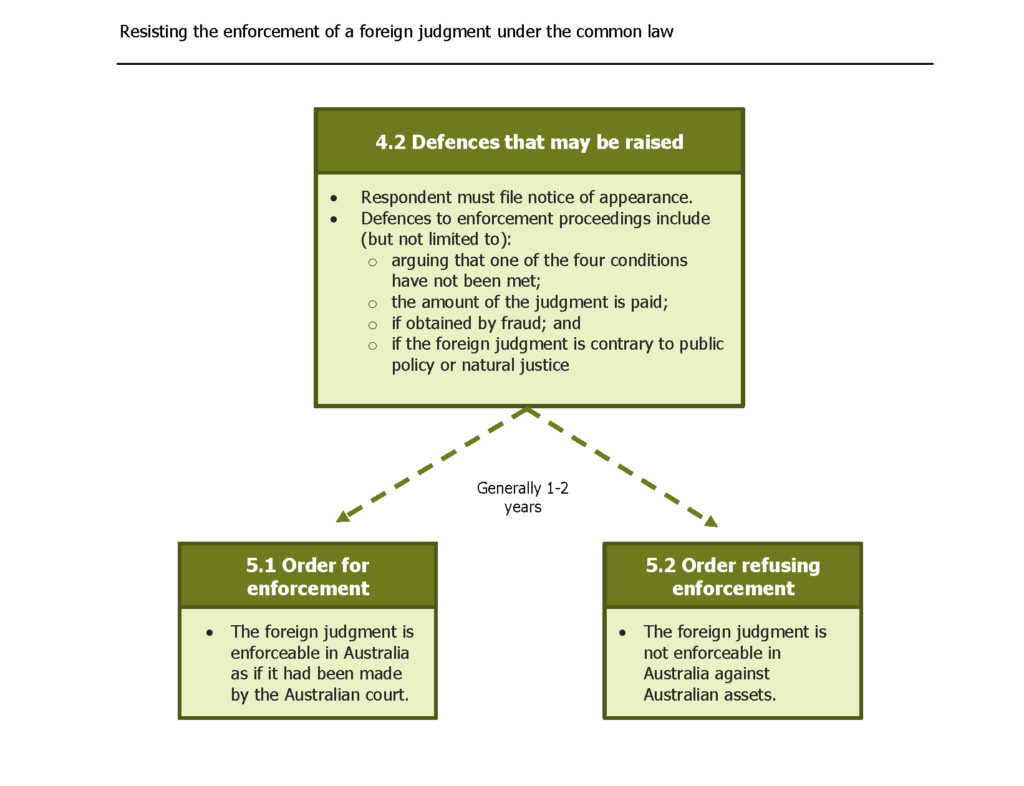

Schematic charts illustrating the various processes are set out in Schedules 1-4 (refer to the foot of this article).

Enforcing foreign judgments in Australia: the FJA

Notwithstanding the recent changes to Australian insolvency and corporation laws in response to the COVID-19 crisis, creditors still maintain the right to enforce debts against companies or individuals through the courts.

The FJA establishes a statutory scheme under which both final and interlocutory judgments of foreign courts can be registered and enforced in Australia.

Requirements

For a foreign judgment to be enforced under the scheme, it must be:

(a) from a court that is specified under the FJA and the Regulations;

(b) final and conclusive;

(c) for the payment of a sum of money;

(d) not wholly satisfied; and

(e) enforceable in the country of the original court.

The scheme is restricted to judgments from the listed ‘superior courts’ of the jurisdictions set out in the Schedule of the Regulations, or certain specified ‘inferior courts’.

Judgments in respect of taxes, fines or other penalties can only be enforced under the FJA if they relate to New Zealand or Papua New Guinea tax matters. The FJA does not allow for the enforcement of judgments from other jurisdictions in respect of these matters.

‘Final and conclusive’ means the judgment must settle the dispute between the parties. Although a judgment may still be considered ‘final and conclusive’ if it is subject to an appeal, an Australian court may choose to stay the enforcement of the judgment until the appeal has been determined. This extends to circumstances where the appeal has not yet been made, but the court is satisfied that a debtor intends to make an appeal.

Registration

For the vast majority of monetary judgments,[3] the appropriate court to apply to for registration is the Supreme Court in any Australian State or Territory. Each State and Territory has similar provisions in their respective civil procedure rules.

Time limitations

Applications for registration must be made within six years of the date of judgment or, if the judgment has been appealed, from the date of the last judgment in the appeal proceedings.

Process

Before commencing registration proceedings, relevant credit, security and company searches should be conducted insofar as practicable to see if the debtor has sufficient assets in Australia to justify the costs of continuing with registration and to check that there has been no undue disposal or transfer of assets by the debtor.

This may include searches for real and personal property, security interests, shareholder and directorship searches, as well as litigation and credit checks.

Registration proceedings are commenced by originating application and can be made without notice to the debtor (although the court has discretion to order that notice be given).

Generally, the application must be supported by an affidavit that evidences, amongst other things:

(a) a copy of the original court’s judgment, certified by the original court, under its seal;

(b) particulars of the costs incurred by the applicant for registration;

(c) the exchange rate, if the judgment is in a foreign currency;

(d) the rate of interest applicable; and

(e) if the judgment is not in English, a translation of the judgment which is certified by a person who is competent to make the translation into English (typically, a NAATI[4] accredited translator).

At the date of writing, the filing fee for a registration application in the Supreme Court of Queensland is $1,982.90 (for a corporation) or $1,002.90 (for an individual).

If the requirements are satisfied, the FJA requires the court to make an order registering the judgment. This process can be relatively quick as the application may be dealt with in Chambers by the court (i.e. no hearing necessary).

Challenging registration

Once registered, the party who registered the judgment (the creditor) must serve a notice of registration on the debtor.

Any application by the debtor to have the registration set aside must be made within the period specified by the particular court and accompanied by an affidavit that sets out the grounds on which the registration should be set aside.

The grounds on which the debtor can seek to set aside registration include that:

(a) the requirements of registration were not properly met;

(b) the judgment was obtained by fraud; or

(c) enforcement of the judgment would be contrary to public policy.

Importantly, a creditor cannot enforce the judgment until the expiry of the period within which the debtor may appeal the registration.

A debtor may also decide to appeal the foreign judgment in the foreign court, and in that case they may also need to apply to stay the enforcement of the foreign judgment in Australia.

Enforcement

If the debtor does not apply for the registration to be set aside, then the judgment is simply registered and ready to be enforced.

The foreign judgment is enforced in the same way as a judgment of the relevant Australian court. In Australia, this can include garnishee orders, the seizure and sale of real and personal property, instalment orders and the appointment of receivers.

Enforcing New Zealand judgments in Australia: the TTPA

The recognition and enforcement of New Zealand judgments in Australia is governed by the TTPA.

Requirements

A New Zealand judgment can only be enforced in Australia if it is registered in Australia.

A judgment will only be registered if it is considered a ‘registrable NZ judgment’. For civil proceedings, this requires that the judgment is a final and conclusive judgment which has been given in a civil proceeding by a New Zealand court or by a New Zealand tribunal that is prescribed by the Trans-Tasman Proceedings Regulation 2012 (Cth) (TTPR) and is of a particular kind prescribed by the TTPR.

Time limitations

An application to register a New Zealand judgment under the TTPA in Australia must be made within six years after the day the judgment is given or, if there have been appeal proceedings, within six years of the day of the last judgment in those proceedings.

Process

To commence an application, a creditor can simply file a statutory form in a superior Australian court or an inferior Australian court that has the power to grant the relief in the judgment or impose a civil pecuniary penalty of the same value imposed by the judgment. A copy of the New Zealand judgment certified by the original court (or otherwise authenticated) must also be filed.

Challenging enforcement

If the application is approved, the Australian court issues a Certificate of Registration of Judgment, which should be served on the debtor within 15 working days of the registration order being made.

Unlike registration under the FJA, a New Zealand judgment registered under the TTPA can be enforced as soon as the notice of registration is given or, even if no notice of registration is served, after 45 working days.

A debtor has 30 days after receiving a notice of registration to apply for a stay of enforcement if they intend to apply to set aside, vary or appeal the judgment in New Zealand.

Alternatively, a debtor may also challenge the registration of the New Zealand judgment within 30 days on the grounds that:

(a) enforcing the judgment is contrary to public policy;

(b) the judgment was registered in contravention of the TTPA; or

(c) the judgment was given in a proceeding relating to immovable property, or was given in a proceeding in rem the subject matter of which was movable property and that property was not in New Zealand at the time of the proceeding in the original court.

Enforcement

Once registered, a New Zealand judgment can be enforced in the same manner as an Australian judgment.

Enforcing foreign judgments in Australia: common law

If a foreign judgment cannot be enforced under the FJA, a creditor must rely on common law principles.

Requirements

There are four requirements under the common law that must be satisfied for a judgment to be enforced:

(a) the foreign court must have exercised a jurisdiction which the Australian courts recognise;

(b) the judgment must be final and conclusive;

(c) the parties to the judgment and the application must be identical; and

(d) the judgment must be for a fixed or readily calculable debt.

Time limitations

The limitation period under the common law is dependant upon the State in which the application is made. For example, in New South Wales and Queensland the limitation period is 12 years from the date on which the judgment becomes enforceable in the country in which the judgment was made, but can be up to 15 years in other States and Territories.

Process

A creditor must bring an entirely fresh action in the appropriate Australian court to enforce a foreign judgment. Such an action can be brought either as an action for a debt, or as the original cause of action for which the judgment was obtained.

If the creditor chooses the latter option, they can rely on the foreign judgment to create an estoppel in relation to any defence raised by the debtor. This prevents the debtor from relying on any defence which was either raised, or could have been raised, during the original foreign proceedings.

One significant difference in registering a foreign judgment under common law principles as opposed to under the FJA is that the creditor must serve the statement of claim on the debtor (i.e. a creditor cannot obtain a more simple ex parte registration of a foreign judgment). If no defence is received from the debtor, the creditor can then apply for a default judgment.

Challenging enforcement

A debtor can rely on five recognised grounds to apply to have the enforcement of a common law judgment refused. These grounds are:

(a) one of the four conditions set out in paragraph 40 above have not been met;

(b) the foreign judgment was obtained by fraud;

(c) the foreign judgment is contrary to Australian public policy;

(d) the foreign court failed to act in accordance with natural justice or to apply the appropriate law; and

(e) the foreign judgment is penal or a judgment for a revenue debt.

Enforcement

A registration of a judgment under common law is able to be enforced in the same way as any other Australian judgment.

Enforcing Australian judgments overseas

The procedure for enforcing an Australian judgment in a foreign jurisdiction will vary from country to country, particularly as Australia is not a party to the Hague Convention onRecognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters 1971, and so can be difficult to navigate from Australia.

Where Australia has reciprocal enforcement arrangements with the country in question, the process is often streamlined and certain prerequisites to enforcement are likely to be similar across these countries. The jurisdictions with which Australia has reciprocal enforcement arrangements are essentially those that are included in the Regulations.[5]

Some common prerequisites for these countries are that the application to the foreign court includes:

(a) copy of the Australian judgment certified by the Registrar;

(b) if necessary, a translation of the judgment; and

(c) a supporting affidavit that specifies the identification of the defendant and states the sum payable in the currency of that country.

For those jurisdictions that do not have reciprocal enforcement arrangements with Australia, such as China and the United States, the process may vary significantly, as will the likelihood of successful enforcement. For example, should you wish to enforce an Australian judgment in the United States, the general process is to begin a fresh law suit for the underlying debt the subject of the foreign judgment.

Arbitration awards

Arbitration provisions to deal with dispute resolution, including in relation to debts, are increasingly common in international agreements.

A party who is successful in obtaining an arbitral award in its favour can then apply to a court in any country that is a party to the New York Convention. As at May 2020, 163 countries are party to the New York Convention.

The fact that the number of countries which are a party to the New York Convention is far more extensive than those included under the FJA regime makes this mechanism an important tool in the resolution of debt disputes in the international market.

Conclusion

The process of enforcing foreign judgments can be simple and streamlined, or quite complex, depending on the country in which the judgment was obtained. Decisions on the appropriate jurisdiction to institute proceedings should be made with this in mind, and proper legal advice should always be obtained.

A further lesson to learn from this is the importance of proper drafting of agreements from the outset. Agreements should identify clear guidelines on the governing jurisdiction if a dispute arises, and if it is an international agreement, parties should consider referring disputes to arbitration to improve their opportunities to enforce an award made in their favour.

Schedule 1

Schedule 2

Scheduled 3

Schedule 4

[1] They are: Alberta; the Bahamas; British Columbia; the British Virgin Islands; the Cayman Islands; Dominica; the Falkland Islands; Fiji; France; Germany; Gibraltar; Grenada; Hong Kong; Israel; Italy; Japan; Korea; Malawi; Manitoba; Papua New Guinea; Poland; St Helena; St Kitts and Nevis; St Vincent and the Grenadines; Seychelles; Singapore; the Solomon Islands; Sri Lanka; Switzerland; Taiwan; Tonga; Tuvalu; the United Kingdom; and Western Samoa.

[2] There is also a separate treaty with the United Kingdom called the Reciprocal Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters 1994.

[3] If the judgment is a money judgment and was given in proceedings in which a matter for determination arises under the Commerce Act 1986 of New Zealand (other than proceedings under particular sections of that Act) a judgment debtor may apply to either the Federal Court of Australia or the Supreme Court of a State or Territory.

[4] National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters.

[5] See footnote 1, above.