Progressive amendments to the Residential Tenancies and Rooming Accommodation Act 2008 (Qld) (Act) have been introduced since 2021. From 1 October 2022, the Housing Legislation Amendment Act 2021 (Qld) (HLA Act) will introduce changes to repair orders and renting with pets, but more importantly will significantly alter termination rights under residential tenancy agreements[1] – including the removal of notices to leave without grounds.

These reforms will have a significant impact on all residential landlords (and tenants), including community housing providers (CHPs) who deliver important housing opportunities across Queensland. To date, many CHPs have allowed tenants to occupy properties on a ‘periodic’ (i.e. month to month) agreement, however from 1 October 2022 CHPs should consider shifting to requiring fixed term agreements where a notice to leave without grounds may previously have been given to a tenant (for example, for headleased properties, including shorter term government headleases such as Help to Home).

In this article, we explore the changes that are coming into effect from 1 October, the implications for headlease scenarios (commonly used by CHPs) and the issues that should be considered and addressed – with a summary and key recommendations at the end.

Ending residential tenancy agreements

Until 30 September 2022

The Act sets out the various notices to leave that a lessor may give[2]. Included in these is a ‘notice to leave without ground’ (section 291), which can be given by the landlord at any time (though cannot be given where doing so would constitute retaliatory action, or where certain other steps have been taken by the tenant to protect their rights).

While a notice to leave without ground can be given at any time, the handover date is the later of 2 months after the notice is given or the day the fixed term agreement ends (section 329).

For current tenancies, a notice to leave without ground (for both fixed term and periodic tenancies) can be given up until 30 September 2022.

From 1 October 2022

The HLA Act reforms a number of termination rights, but the most important is replacing the ‘notice to leave without ground’ with a ‘notice to leave for end of fixed term agreement’. Under the revised section 291, a landlord may terminate a residential tenancy agreement if it ‘is a fixed term agreement and the notice relates to the end of the agreement’.

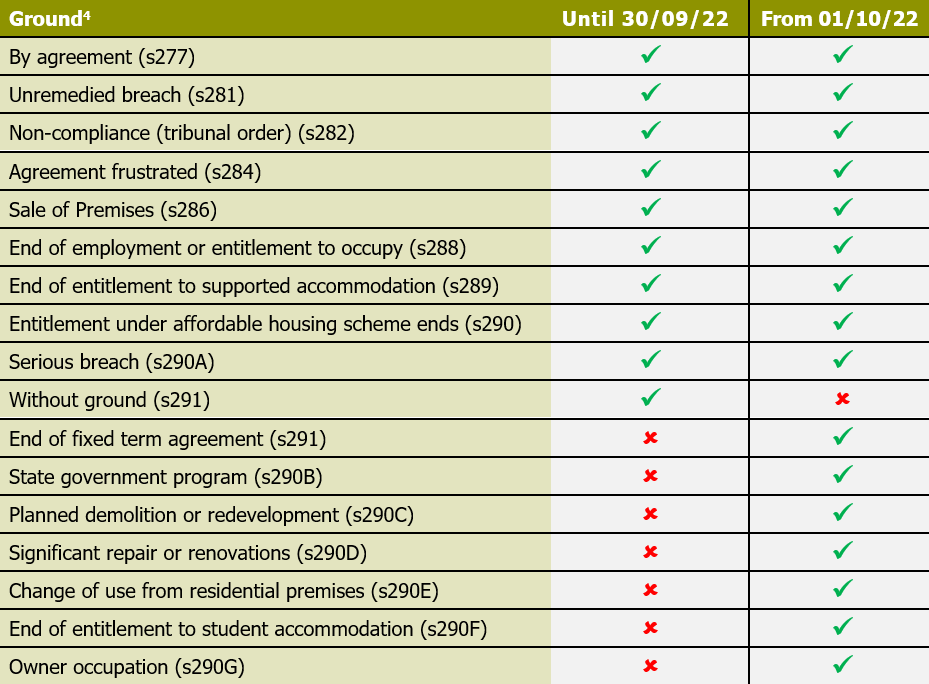

The effect of this is that a periodic agreement (including a fixed term agreement that has become a periodic agreement – see section 70 of the Act) cannot be terminated without ground. Rather, it can only be terminated by agreement or as a result of another notice given under the Act (and a number of additional grounds have been added)[3]. A summary of the grounds for termination, both until and from 1 October 2022, is below.

While the removal of the notice to leave without ground for periodic tenancies is intended to provide additional certainty to tenants (to ensure they are not at ‘risk’ of landlords terminating without reason), we expect to see private landlords shift to require all tenants to be on fixed term agreements, in order to preserve their right to end the agreement without needing to rely on one of the specific grounds for termination.

Where a tenant refuses to enter into a fresh fixed term agreement (at the end of their existing agreement), we expect that private landlords will consider issuing a ‘notice to leave for end of fixed term agreement’ and source a replacement tenant, which may simply act to drive up rental turnover and instability. While a landlord is still prohibited from giving such notice where it would constitute ‘retaliatory action’[5], we do not consider that this would be triggered in these circumstances.

For CHPs, who provide crucial support to members of the community requiring housing solutions, we expect that CHPs may not wish to place all tenancies under fixed term agreements unless there are sound reasons to do so. CHPs will need to balance providing stable housing for their tenants against protecting their own viability and legal responsibilities. CHPs may also have contractual obligations (for example with the State) which may impact these decisions.

Headleases

Background

As discussed above, the HLA Act reforms are likely to shift practices for all landlords, and present some challenges for CHPs in balancing their objectives and risks. Unfortunately, CHPs will face a further complication where arrangements involve a headlease (including under the Community Rent Scheme).

Most headleases, particularly to CHPs, will not necessarily be governed by the Act or considered a ‘residential tenancy agreement’, since it will typically not give the CHP the right to occupy the premises as a residence. Given this, there is wide variation in the terms of headleases, with each CHP (and potentially each landlord) having their own form.

Headlease structures are not contemplated by the Act (or the HLA Act). For example, there is no right under the Act to terminate a residential tenancy agreement as a result of the ending of a headlease. Further, a headlandlord’s termination rights under a headlease will likely differ from a CHP’s termination rights under a residential tenancy agreement sublease. This distinction is most important where the headlease requires the CHP to provide vacant possession at expiry – a provision which is likely to be included in all headleases.

Inconsistency

This critical disconnect between the headlease and sublease could leave CHPs in breach of the headlease. For example, where a landlord validly terminates a headlease after 1 October 2022 and the CHP has let the premises to a tenant under a periodic lease, there may be no grounds for the CHP to terminate the residential tenancy agreement (and provide vacant possession to the headlandlord).

Even in circumstances where the headlease is drafted to contemplate termination only in accordance with the Act, there may be a disconnect. For example, if the headlease is a fixed term lease and the sublease is periodic, CHPs would still potentially be unable to terminate the sublease. For this reason, we encourage CHPs to ensure that the tenure of the headlease and sublease align.

Further issues

Secondly, some of the new grounds for termination (i.e. for sale[6], change of use[7] or owner occupation[8]) contemplate the landlord taking an action (i.e. selling, changing the use or needing to occupy the premises). In these circumstances, while the headlandlord may be able to give such a notice, there is an argument that a CHP would not be able to since it is not taking those steps (but rather the headlandlord is).

While the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal (QCAT) may provide relief to CHPs in some of these circumstances, there is no certainty of this, and QCAT may seek to protect the tenant. Such processes also divert CHP resources and can become protracted.

CHP provisions

The Act does contain some specific provisions dealing with residential premises provided by CHPs, for example additional termination rights including for serious breach or end of entitlement under an affordable housing scheme. Of particular note, a notice to leave for ending of housing assistance[9] can be given where a tenant occupies premises under an affordable housing scheme[10] and ceases to be eligible under the scheme to occupy the particular premises. This could allow termination by a CHP where the headlease is terminated by the headlandlord, as the tenant would have no eligibility to continue to occupy the particular premises. However, the exact operation of this provision in such a scenario is unclear and has not been considered in reported decisions from QCAT or courts.

Summary and recommendations

Fixed term agreements

All CHPs should consider the risks posed by the removal of notices to leave without grounds, and in what circumstances they will require fixed term residential tenancy agreements (for example, where a private headlease is in place).

For circumstances where a fixed term agreement is required, CHPs should ensure that they monitor the expiry date of agreements and ensure fresh agreements are entered into prior to expiry, to avoid the agreement inadvertently becoming periodic.

Headleases

For any CHP who provides residential accommodation under a headlease (including as part of CRS or Help to Home), CHPs should review the headlease and consider changes that may be required as a result of the October 2022 changes in order to minimise risk of breaching the headlease or the Act. Particular consideration should be given to:

- obligations to give vacant possession at the expiry or termination of the headlease (private landlords may not be prepared to simply accept a novation of any underlying sublease given it could leave them with a direct lease to the tenant which may have more limited grounds of termination than their headlease);

- the termination rights in the headlease and how those align with the Act – for example:

- does the headlease provide its own separate grounds for termination, or does it seek to align to the Act; and

- if the headlease aligns to the Act, does it allow an additional period above that under the Act (to allow the CHP to give notice to its subtenant) and will it still align after the HLA Act amendments commence on 1 October 2022;

- the tenure (i.e. fixed term or periodic) and how that aligns with any sublease (or anticipated sublease); and

- the indemnities given by the CHP under the headlease (e.g. for failure to provide vacant possession), and any limitations on those (e.g. exclusions where the CHP is prevented from giving vacant possession as a result of the Act).

As each headlease is different, each CHP will need to undertake this assessment itself and the outcome will likely be different for each (and may even be different for each property).

Reforms

Ideally, the complexities created by these amendments under the HLA Act for residential tenancies which operate under headlease arrangements would be addressed by further reforms to the Act. For example, this could be achieved by amending section 290 of the Act to clarify that a notice to leave for end of housing assistance can be given where a headlandlord terminates the headlease.

Of course, CHPs will use their best endeavours to find another housing option for tenants when a headlandlord withdraws their property from the rental market. However, it is important from a best practice perspective that the termination provisions of headleases and residential tenancy agreement subleases (including those under programs such as Help to Home) are aligned, in order to minimise potential breaches.

If you require any assistance in navigating the changes to the Act or any issues raised in this article, including advice on headleases, please contact us.

[1] This article focuses on residential tenancy agreements, however similar provisions apply to rooming accommodation agreements.

[2] Chapter 5, Part 1, Subdivision 2.

[3] Chapter 5, Part 1, Subdivision 2.

[4] Excludes notices relating solely to moveable dwellings.

[5] Section 246A of the Act, introduced by section 52 of the HLA Act.

[6] Section 286 of the Act, as amended by section 56 of the HLA Act.

[7] Section 290E of the Act, as introduced by section 58 of the HLA Act.

[8] Section 290G of the Act, as introduced by section 58 of the HLA Act.

[10] See definition at Schedule 2 of the Act.