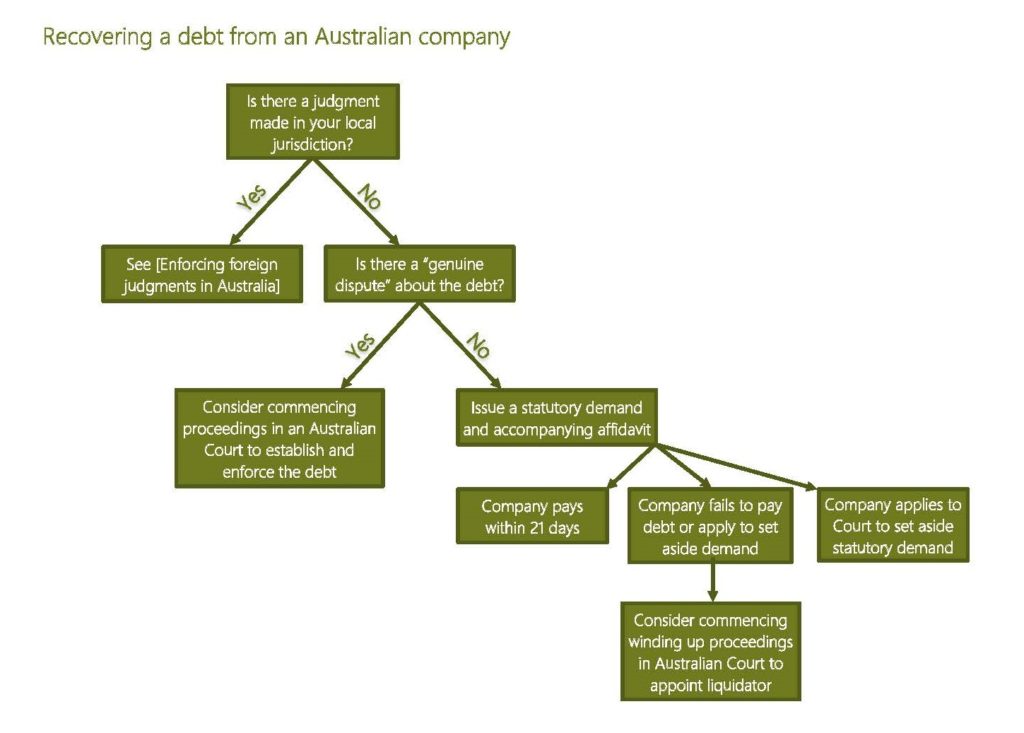

A creditor that has the benefit of a debt of at least A$2,000 may serve a statutory demand on the debtor company. A statutory demand is a formal demand for payment under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The demand must be for over A$2,000. Once a statutory demand has been validly served on a company, the company has 21 days to either:

(a) pay the debt claimed in the demand; or

(b) apply to the Court to set aside the demand.

If the company fails to do so, pursuant to the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), it will be presumed to be insolvent and winding up proceedings can be commenced in Australia.

Important note: In response to the impact of COVID-19, a range of temporary measures have been introduced in Australia changing the law with respect to statutory demands and preventing creditors from winding up companies. Click here to learn more.

What debts can be relied on to issue a statutory demand?

A debt the subject of a statutory demand must be over A$2,000 (if more than one debt is owed, the debts must total more than A$2,000) and be due and payable.

Unliquidated debts cannot be the subject of a statutory demand.

If the debtor company owes more than one debt to the creditor, the creditor is not required to issue a demand for each debt, but can issue a single demand specifying the total debt and how the debts have arisen.

The statutory demand process is not confined to debts payable in Australia, nor are there any requirements for a statutory demand to specify a place in Australia at which payment of the debt must be made. A foreign debt can be expressed in the statutory demand in foreign currency, although best practice is to state the foreign currency amount and to also provide the Australian dollar equivalent.

A foreign judgment, including an unregistered foreign judgment, can be used as a basis for issuing a statutory demand. However, if the judgment is unregistered, common law defences can be raised to argue that the statutory demand should be set aside (for example, on the basis that the judgment was obtained by fraud, is contrary to Australian public policy, is contrary to natural justice or is penal). A common process is therefore to have the foreign judgment registered in Australia and then to issue a statutory demand.

Requirements of a statutory demand

The statutory demand must:

(a) specify the debt and its amount;

(b) require the company to pay the debt within 21 days after the demand is served on the company;

(c) be in writing;

(d) be in the prescribed form (Form 509H as set out in Schedule 2 to the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth));

(e) be signed by or on behalf of the creditor; and

(f) be accompanied by:

i. the judgment of the Court that relates to the debt (if the debt is a judgment debt); or

ii. an affidavit that verifies that the debt is due and payable by the debtor company (if the debt is not a judgment debt).

If the demand does not comply with these requirements, it may be set aside by the Court upon the application of the debtor.

Service of statutory demand

A statutory demand must be formally served on the debtor company. This can be achieved by:

(a) leaving the statutory demand at the registered office of the company;

(b) sending the demand by registered post to the registered office of the company; or

(c) delivering the demand personally to a director of the company who resides in Australia.

The address for payment of the debt and the address to serve any application to set aside the default judgment must be in the same jurisdiction in which the statutory demand is served. That is, if you serve a statutory demand on a company in New South Wales, Australia, the demand must include an address for service in New South Wales, Australia.

Setting aside a statutory demand

The debtor company can apply to the Court within 21 days of the demand being served, to have it set aside on certain grounds, including that:

(a) there is a ‘genuine dispute’ about the existence or amount of the debt (this is not a high threshold to meet, but is unlikely to be met where the foreign judgment is registered);

(b) the debtor company has an offsetting claim;

(c) substantial injustice will be caused unless the demand is set aside because of a defect in the demand (e.g. misstatement of an amount or a misdescription of a person or company); or

(d) the Court is satisfied that there is some other reason why the demand should be set aside.

To set aside the statutory demand, the debtor company must file an affidavit in support of the application with the Court and a copy of the application. A copy of the supporting affidavit must be served on the creditor.

If the debtor company is successful in setting aside the demand, the Court may order the creditor to pay the debtor company’s legal costs in relation to the application to set aside the demand.

Consequences of non-compliance with a statutory demand

There are serious ramifications if a company fails to comply with a statutory demand. In particular, the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) provides that a company is presumed to be insolvent from the date of the expiry of the statutory demand.

If the debt is not paid and no application is made by the debtor company to set aside the statutory demand, a creditor has 3 months to apply to the Federal Court or a State Supreme Court for an order that the company be wound up on the grounds of insolvency. A liquidator can then be appointed to wind up the company and to distribute its assets.

Alternatives to issuing a statutory demand

A foreign company seeking to recover a debt from an Australian company can also commence proceedings in an Australian Court to recover the debt. This option is often preferable where there is likely to be a ‘genuine dispute’ regarding the existence of the debt or the debtor has an offsetting claim.

Please note: Click here for ‘Enforcing foreign judgments in Australia’.